Stand by Me (1986)

Revisiting the Seminal '80s Classic & Exploring What It Can Still Teach Us Today

A Coming-of-Age Classic Like No Other

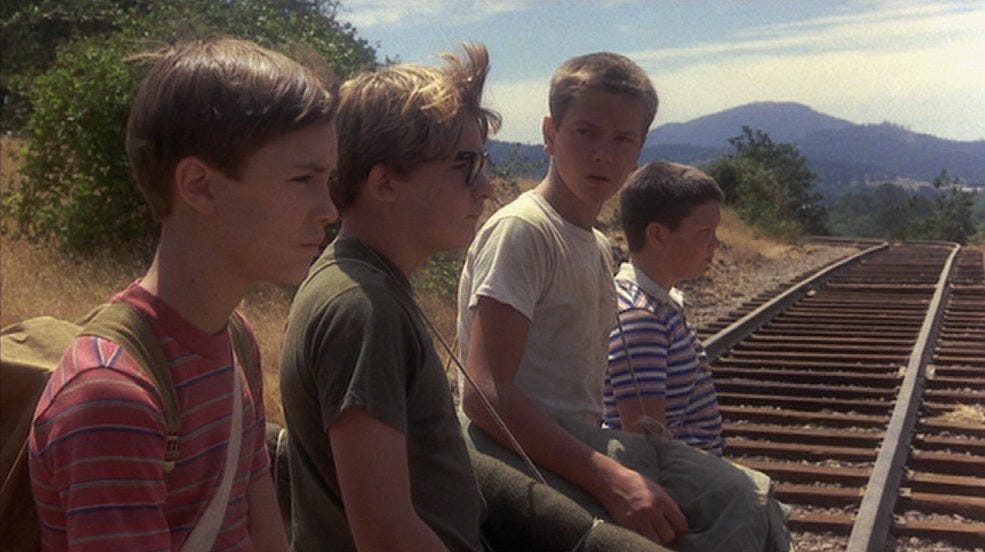

The first time I watched Stand by Me, director Rob Reiner’s 1986 coming-of-age classic, I remember being hit hard by something I wasn’t expecting: its emotional honesty. The film follows four boys on a two-day journey to find the body of a missing local boy, but what starts as a simple adventure story quickly becomes something deeper—a heartfelt statement on friendship, grief, and growing up. It’s a film that’s unafraid to lean into its big feelings—something especially rare in a story of boys and boyhood.

An R-Rated Film Every Teen Should See

Boys aren’t always allowed to cry. They’re told to be strong, to “man up,” to tough it out. But Stand by Me refuses to be bound by those unhealthy stereotypes. It allows its four young protagonists—Gordie, Chris, Teddy, and Vern—freedom to experience a full, healthy spectrum of human emotion. They fear, they grieve, they share secrets, and most importantly, they lean on each other. Watching their journey unfold, I couldn’t help but wonder: why don’t we see this more often?

The film succeeds in large part thanks to its compassionate, respectful understanding of adolescence. Vulnerability is never treated as weakness; it’s just another part of growing up. Each of the boys confronts his own insecurity, fear, or grief, and the film gives them ample breadth to process those feelings.

What’s even more striking is that Stand by Me carries an R rating—for language and mature themes—even though it’s exactly the kind of movie every tween should see. In a sea of sanitized content aimed at kids, it’s a rare film that speaks to them honestly—one which understands that life is messy, and that fostering healthy emotional intelligence is an essential part of growing up. Stand by Me shows us that it’s okay to feel, to stumble, to not have all the answers. And maybe that’s a lesson we all need at thirteen.

The Heart of the Story: Gordie & Chris

Of our core group, it’s the bond between Gordie and Chris that lends the story its beating heart. Still grieving the death of his older brother Denny, whom their parents clearly favored, Gordie is invisible at home—having lost the only person who ever really understood him. Chris breaks that silence. He doesn’t just see Gordie—he believes in him. In his ideas. In his talent. In his worth. Gordie doesn’t know how to ask for that kind of affirmation. But Chris offers it freely.

Chris carries his own burdens—poverty, a broken home, a town that’s written him off as a lost cause—but he’s remarkably clear-eyed for his age. He tells Gordie the truth—not just about writing, but about life: that he doesn’t have to be who his parents say he is. The moment lands not because it’s some clichéd speech, but because it’s earned—Chris knows what it’s like to be discounted. He isn’t just lifting Gordie up; he’s showing him what’s possible.

And it goes both ways. When Chris admits that he's scared he’ll never outrun the lingering specter of his family reputation, it's Gordie who pushes back—encouraging him to pursue college prep courses and fight to reclaim his narrative. You don’t often see that sort of mutual recognition represented in boys’ stories.

Maybe that’s why their bond feels less like friendship than brotherhood. They're not simply surviving together, they're bringing out the best in each other—and in doing so, modeling a healthier approach to masculinity than you’d normally find in an ‘80s film. One defined not by dominance or bravado, but by empathy and compassion—something which, even now, boys rarely get to see reflected back at them in media.

The Emotional Undercurrent: Teddy and Vern

Of course, if Chris and Gordie represent the film’s emotional core, Teddy and Vern serve as an emotional undercurrent—a lens which brings the central message into focus. Teddy is all sharp edges, volatile and occasionally erratic. This tough, fiercely defiant exterior masks deep physical and emotional scars left by his unstable, often abusive father. He’s a kid who’s internalized violence to the point it's become his first—and only—language. But even he breaks down eventually. That moment at the junkyard, when an insult cuts a little too close—suddenly he’s just a frightened kid who wants nothing more than his father’s love.

Vern is the opposite—soft, scared, always trailing behind. He doesn’t pretend to be brave; he just wants to belong. And while he’s often comic relief, he’s also the one who most clearly reflects the more relatable, day-to-day insecurities of adolescence. His arc isn’t one of confronting past trauma; it’s about learning to trust in himself and in the strength of his friends. In that way, Vern reminds us that real strength isn’t always dramatic; sometimes, it’s simply admitting you’re scared—and trusting your friends to help you through.

Together, Teddy and Vern form a counterweight to Chris and Gordie. They don’t have the same introspective arcs, but they’re just as essential to the group’s chemistry. They remind us that not everyone is ready—or able—to meet the world openly. Some feign toughness. Others shrink inward. But all of them are trying to make sense of complex feelings they don’t fully understand and can’t quite express.

Strength in Vulnerability: The Film’s Enduring Lesson

Stand by Me uses these moments of raw, emotional honesty to highlight that openness and vulnerability aren’t things to shy away from. The boys are allowed to feel fully—their anger, fear, anxiety, and grief are all given the space and respect they deserve. It’s rare and wholly refreshing to see a story about boyhood that doesn’t force its leads into some tough, stoic mold. Instead, it just lets them be human.

That’s the magic of Stand by Me. It doesn’t simply paint a portrait of the mid-century American childhood; it gently challenges our own preconceived notions about what it means to be a man. In a culture that often equates manhood with toughened stoicism, rugged individualism, and emotional constipation, Reiner’s film suggests something far more unexpected: that growing up—or really, “being a man”—isn’t just about projecting strength. It’s about learning to understand and embrace the full range of emotions that come with it.

There’s something deeply affecting about how the film handles its emotional beats—not with grand monologues or sweeping orchestrations, but with gentle restraint. When Chris breaks down about the milk money, or Gordie confesses he wishes it had been him who died, Reiner resists the urge to sentimentalize. These boys are allowed to be raw, confused, and unfinished—precisely what makes those moments feel real.

In a lesser film, such moments might be reduced to a narrative footnote or simply dismissed outright as weakness. But Stand by Me affords them compassion and dignity—casting them as just another part of the human experience.

Quiet Rebellion in an ‘80s Landscape

Situated in the broader canon of ‘80s movies—a decade well known for its over-the-top macho excess—Stand by Me feels like a sort of quiet rebellion. Maybe that’s why it hits so hard. Too often, movies present boys as either hardened “John Wayne” archetypes, or simple comic relief—not as emotionally complex people with their own rich inner lives.

But Stand by Me refuses to flatten its protagonists. It’s a film which gives us permission to feel—to fear, to grieve, to love. One that reminds us that coming-of-age isn’t about learning to outgrow our feelings, but about finally figuring out how to carry them.

It’s a testament to Reiner’s skilled direction that, for all its heavy, complex themes, Stand by Me never ends up feeling like a lecture. His film smartly understands that the message doesn’t need to shout to make itself heard. Instead of spelling everything out, he lets his themes live in the quiet spaces—in a glance, a pause, a shared silence between friends. The film trusts its audience to feel what it’s saying: that there’s strength in feeling deeply, in caring deeply. That there’s bravery in being there for your friends. That there’s nothing unmanly about needing someone.

A Lesson Worth Holding On To

And that cuts to the heart of why the film endures—not because it romanticizes youth, but because it respects it. It treats the emotional lives of boys with seriousness, compassion, and grace—a quality still far too rare in boys’ stories. By giving its characters space to be scared, to be gentle, to lean on each other, the film quietly dismantles the lie that growing up male means learning to bury one’s emotions. It insists that real strength isn’t found in silence or stoicism, but in connection, vulnerability, and the courage to care honestly and openly.

In a modern media landscape that continues to favor traditionally rigid ideas of masculinity and manhood, Stand by Me still feels radical. As a film, it presents an alternative—a model of boyhood grounded not in posturing, but in empathy. And in doing so, it offers audiences—especially boys and young men—something far more valuable: not just representation, but permission. Permission to feel. To care. To simply be.

And in a society that continues to wrestle with what, exactly, it means to be a man in today’s world, that’s a lesson worth holding onto—no matter our age.

Stand by Me (1986)

Starring: Wil Wheaton, River Phoenix, Corey Feldman, Jerry O’Connell, and Kiefer Sutherland

Directed by: Rob Reiner

Columbia Pictures

Runtime: 89 minutes

Rated R for language and mature thematic material